When the human genome project was deemed “complete” in 2003, it was met with incredible fanfare. The entire project leading up to that moment had all the drama to keep its audience enthralled. Fierce rivalry between a public and private institution, multiple countries involved, 3.5 billion dollars at stake, and 13 years invested. It was a herculean effort and at the end of all that, we had decoded life itself and now had a map of the human genome. It was the biological equivalent of putting a man on the moon. It was predicted that as a consequence of the human genome project, we would ’’unlock the secret to human life” and revolutionize medicine and our understanding of human health and disease. Even when the “useful life” of projects was considered, the shelf life of the scientific tool produced by the HGP was, effectively, forever.

20 years later, while there are many outcomes to celebrate: the development of an array of new technologies; the generation of highly useful genetic and physical maps of the genome of several organisms; the coupling of a scientific research programs with a parallel research programs in bioethics; and, now, the highly polished sequence of the human genome, free and readily accessible to all– the ultimate promise of the human genome project has not yet been realized. We got nowhere close to curing diseases like we thought we would. So, what’s actually happened since the human genome project?

Cost of sequencing in a free-fall

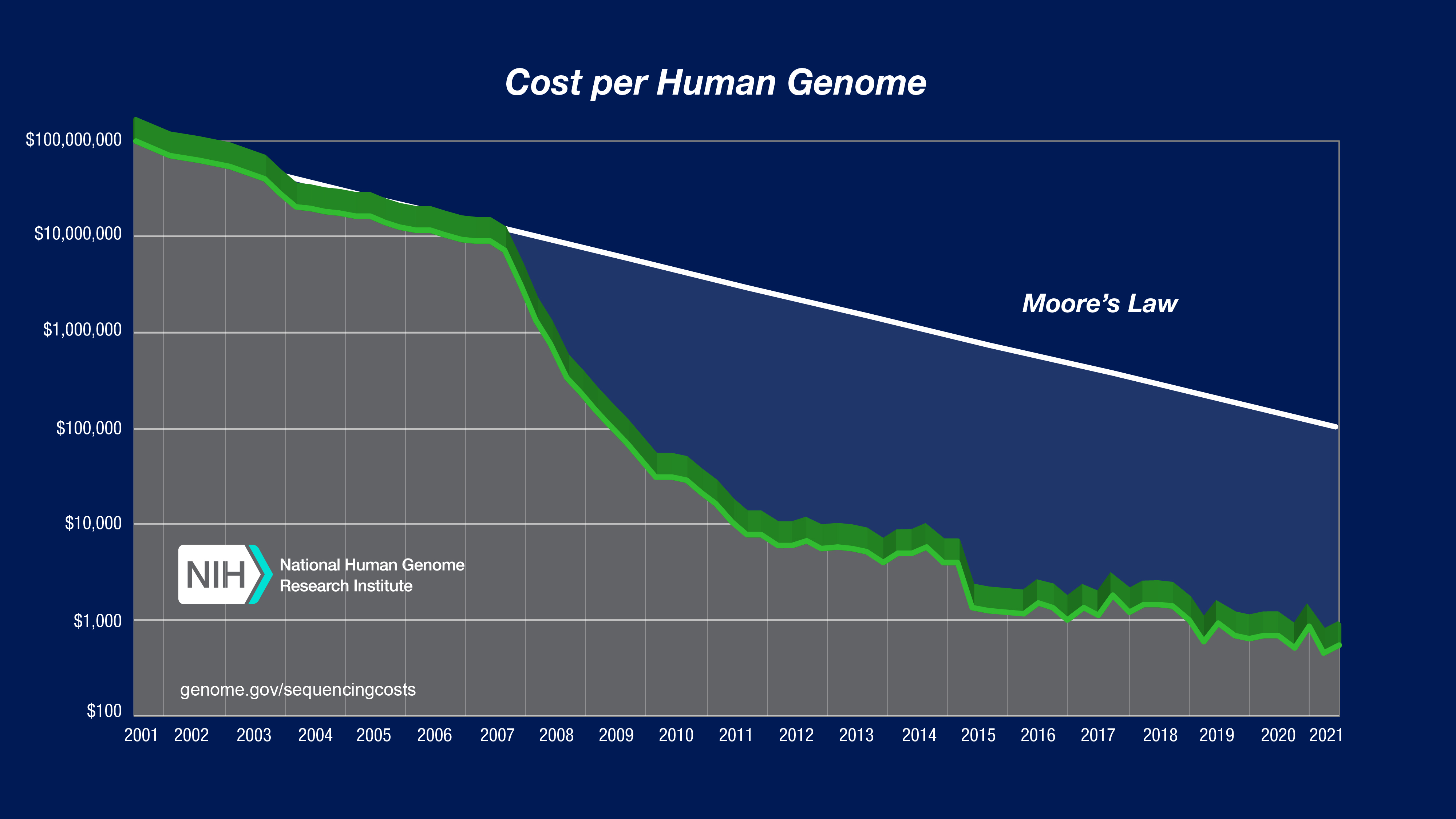

If you’ve ever taken a class in human genomics, you’ve probably seen this image below at least a few dozen times. The cost of sequencing used to be impossibly high and it’s been in a free fall ever since. Bear in mind the vertical axis is on a logarithmic scale, so every vertical unit indicates an order of magnitude drop in cost. The reason it’s so fascinating(horrifying) is because since January 2008 the capacity to generate sequence data has increased much, much faster than Moore’s Law for computing hardware (the gray line in the chart). So, we’ve clearly gotten good at generating lots of data for very cheap, are we any good at storing and analyzing them?

dna-sequencing-cost

Data storage and sharing challenges

A single human genome takes up 100 gigabytes of storage space. And as more and more genomes are sequenced, storage needs will grow from gigabytes to petabytes to exabytes. By 2025, an estimated 40 exabytes of storage capacity will be required for human genomic data. And that’s not all, for every 3 billion bases of the human genome sequence, 30-fold more data (~100 gigabases) must be collected because of errors in sequencing, base calling, and genome alignment.

This means that as much as 2–40 exabytes of storage capacity will be needed by 2025 just for the human genomes. Some researchers anticipate the creation of genomics archives for storing millions of sequenced genomes. Others believe that cloud computing is the only storage model that can provide the elastic scale needed for DNA sequencing.

So far, most of the data generated lives in hacky custom-built databases developed by governments, funding agencies, research institutes and private researchers. And the patchwork of repositories, with various rules for access and no standard data formatting, has led to a “Tower of Babel” situation. In fact this problem is so well known that there’s even an xkcd comic on it.

xkcd-comic

Another challenge is that for genetic data to be useful, it needs to be combined with phenotypic data demographics, medical histories and other identifiable traits that can be linked to variants in the genome. But collecting such data increases privacy risks for research participants, who are now rightly being given more control, such as choosing how their data will be used. Moreover, some scientists worry that sharing data will undermine their ability to get credit for stuff.

Researchers also struggle to track down data that should be available as soon as the accompanying research is published. And even after locating the data, they can find it hard to access them. Mostly because the process to submit and access data is extremely tedious and annoying usually involving filing multiple rounds of digital paperwork, submitting letters of support and detailed proposals only to find dead ends or unusable files.

Biology too complex

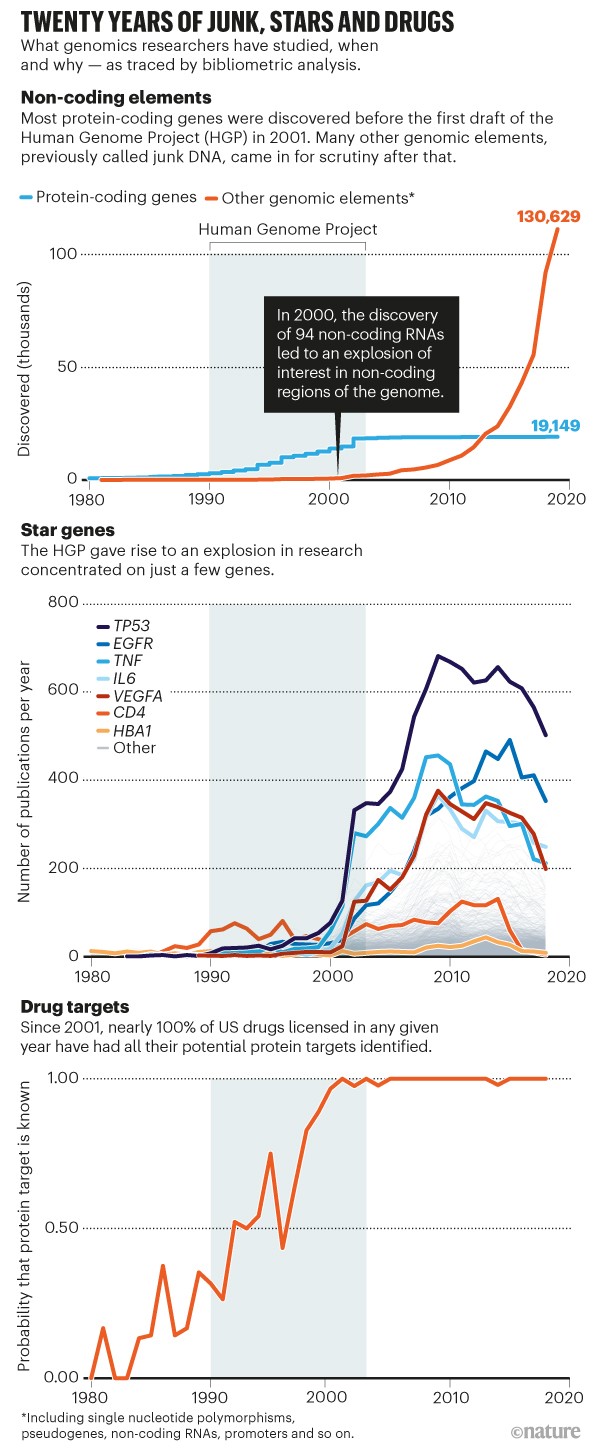

It was predicted that knowing the function of every gene was going to change everything. The general notion was that if we could parse its meaning then we could perhaps start to decode our genetic future and predict and prevent diseases before they even began. It seemed like medicine had finally found the holy grail of genetic therapy and so countless startups, big pharmaceuticals and universities alike joined in the new gold rush. Millions of dollars were invested in huge projects like ENCODE (Encyclopedia Of DNA Elements) Project and Cancer Genome Atlas Project where instead of looking at a single human genome, these projects would sequence more than ten thousand genomes to hunt for new variations in diseases. But surprisingly, that did little to move us closer to our understanding of the disease. Turns out, even basic concepts such as ‘gene’ and ‘gene regulation’ are far more complex than we’d ever imagined. For example, for the longest time, there was no consensus on where a gene starts and ends or, surprisingly, even what sequence exactly encodes some genes.

Rich genes got richer

You would think that when a gene is well studied, we would want to explore other parts of the genome. But the opposite happened. More attention was given to just a select few. Apart from biology being too complex, there was another problem. It seems that even among genes, the rich get richer. Since 2003, several researchers have noticed that scientists tend to study genes that are already well studied, and the genes that become popular aren’t necessarily the most biologically relevant ones. In fact, in a study in 2017, they found that 22% of gene related publications referenced just 1% of the genes.

Part of the reason for this is erosion of funding in biomedical sciences which forces researchers to compete against one another for dwindling grants and pushes them towards safer research and other times, studying new genes takes an extremely long time and can consume entire careers. For example, researchers will spend years engineering lab rats and find out that the rats lack the gene in question lol.

static

Game changer for rare diseases

It wasn’t all bad news though. It’s hard to overstate just how influential human genome drafts were for rare diseases, especially those caused by single mutation.

But what’s so special about rare diseases?

Well, we know that about 80% of rare diseases have a genetic component to them so it makes sense that sequencing the entire genome might increase the potential to uncover an underlying etiology in a patient.

But how do you go from sequencing a genome to identifying potential rare disease-causing variants?

You might start by comparing the entire genomes of people who suffer from an unknown disorder, to see if they have variants in common. You could then dismiss most of those variations—either they corresponded to already known conditions, or they occurred frequently enough in the general population to rule out their being the cause of a rare disease, or they were involved in biological processes that were unrelated to the patient’s symptoms. This might leave a short list of about a dozen genes. If you’re left with one gene in common, voila! There’s your single mutation disease causing gene. This way, researchers were able to identify potential disease-causing variants across the genome much more rapidly than had previously been possible. Thanks to it, the number of single mutation diseases that have a known genetic cause went from 1,257 in 2001 to 4,377 at the time of writing (according to the OMIM database, an online catalog of human genes and disorders; go.nature.com/omimdb).

So, that’s pretty impressive.

Patients are now increasingly liberated from the long-standing diagnostic bottleneck. Many can receive a diagnosis quickly, with a precision that remains unparalleled in medicine. This is one area where we have come closest to true personalization of disease management.

Diversity deficit

In the years since the Human Genome Project published its first draft sequence, there’s growing recognition that genome databases over-represent DNA from people of European descent who live in high-income nations. We need data that properly represent humanity’s vast genetic diversity in order to get better at picking up diseases that are more prevalent among specific ethnic groups. The fact that this has not been achieved in two decades is a reminder of science’s history of mistreatment and neglect, particularly of African people and Indigenous populations. There is work being done here to improve genetic resources for individuals with African ancestry in recent years but many people from these communities are understandably wary of participating in research that they regard as having little chance of benefiting them, and even some chance of causing harm. For example, when diseases are associated with a particular population, it can result in stigma and discrimination.

What is to come?

With more data available, the grand scientific challenges of our day turns into something more like a computational puzzle: how can we integrate billions of base pairs of genomic data, and 10 times that amount of proteomic data, and historical patient data, and the results of pharmacological screens into a coherent account of how somebody got sick and what to do to make them better? This is a good problem to have and breakthroughs are happening everyday. Google recently made a splash earlier this year with their new method called PEPPER-Margin-DeepVariant – that can identify likely disease-causing variants in less than 8 hours after sequencing, compared to the prior fastest time of 13.5 hours. I suspect there will be more like this in the coming months.

Today we're sharing research from @StanfordMed on how the genome sequencing method we built with @ucscgenomics helped speed up identification of disease-causing variants, enabling faster NICU diagnoses. #GoogleAIhttps://t.co/IhzBKa0oun

— Sundar Pichai (@sundarpichai) January 13, 2022

Sequencing technology will continue to improve. Yes, genomes will get even cheaper and faster to produce. In fact, Element Biosciences recently announced the launch of their DNA sequencer which will only cost $5-$7 to sequence a billion nucleotides. Imagine getting your entire genome sequenced for the prize of a McDonald’s burger!!

With cheaper and better sequencing, we might even get to a stage where we wouldn’t require a single reference genome, we would have a pangenomic reference sequence that captures the full diversity of human variation. This means establishing a new frontier of scientific discovery, much like the human genome project.

So although things haven’t gone like the way we predicted, I try to remember that we invariably overestimate the short-term impacts of new technologies and underestimate their longer-term effects. Especially with these new technologies, I think this might be the time where we move the needle.

Thanks to Eshan Tewari, Nikhil Krishnan, Vishnu Rachakonda and Tavi Nathanson for reading drafts of this post!